By Rose Ellen O'Connor, Volunteer

Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast with deadly force in

August 2005 and Jane Callen watched the news accounts with horror. Thousands of

people were stranded, injured and dying and pleading for help. Bodies were

floating in the streets. Jane felt compelled to act. She took a three-week

leave of absence from her job as the Economic Information Officer for the U.S.

Department of Commerce and went to the Gulf Coast with the Red Cross.

|

| Jane volunteering as part of the relief efforts for Hurricane Katrina. |

“Seeing those images, how could one not have been moved to

help?” Jane asks.

Since then, Jane, named Montgomery County, Maryland’s volunteer of the year in April, has served in countless ways. She’s climbed a mountain in Nepal to help victims of an earthquake and reached out to survivors of hurricanes in Florida and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Here at home, she volunteers as an Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) and the EMS Lieutenant with the Glen Echo Fire Department, is a member of the Red Cross Disaster Action Team, and sits with the dying in hospice care.

The desire to help is a glue that binds volunteers, Jane

says.

After a long, hot day, looking for survivors, they would

return to their base, collapse into flimsy camping chairs, and each throw back

a Bud Light. Then they would forage for food, opening up a can of whatever they

could find. Jane’s a vegetarian, so finding food could be challenging. Her

fellow volunteers would tease her, asking if she wanted cans containing beans

flavored with bacon. Then they would head to their bedroll and go to sleep on a

concrete floor.

Together, they saw many gut-wrenching scenes. There were the

poor neighborhoods where people were already living on the edge before the

hurricane and now were desperate, their basic needs not being met.

“Part of what made it possible to continue was we were there

for each other,” Jane says. “We stayed in touch long after that trip.”

|

| Jane volunteering as part of the relief efforts for Hurricane Katrina. |

In April 2015, Jane went to Nepal for two weeks after a devastating earthquake. Her team of four spent a day climbing a grueling mountain path to reach a village in need. They made it to the top and a huge earthquake – magnitude 7.3 – struck not far away. Buildings collapsed around them and the path they had taken was buried by dirt and boulders. They treated the most badly injured late into the night. It was an enormous challenge getting the most seriously injured off the mountain. Villages and volunteers worked together to build a fire of rags in hopes that a helicopter would spot them. An Army chopper saw the flames and came.

Late that night, the team tried to get word to their

families back home that they were okay. Aftershocks were coming every few

minutes. They crawled on their hands and knees around the mountain top, waving

their phones in the air, trying to find a signal. No luck. Jane felt physical

pain thinking what her family must be going through.

Around 4 a.m., Jane awoke to dozens of tiny hands on her

tent. Village children were peering in to see who was there. Many of the

children needed attention for injuries and conditions unrelated to the

earthquake because they didn’t have access to proper medical care. The

volunteers got up and tended to the children’s medical needs as best they

could. All the while, Jane could not stop worrying about what her family might

be thinking. Later that morning, a man arrived who had fallen off a motorbike

while ascending the mountain during the second earthquake. He had a cell phone

and the volunteers were thrilled when they realized it worked. Jane called her

husband.

“The fact that I was alive and standing there on that mountain bathed in sunshine, hearing my husband’s voice – it was a brilliant, shining moment,” Jane says.

Jane’s memories of Nepal are flooded with the images of

families standing in front of piles of total wreckage that once had been their

homes. They were smiling. In the midst of disaster, they appeared happy and

grateful to be alive. They welcomed the volunteers as their friends.

“The radiance of the Nepalese,” Jane says, “is beyond even

the reach of an earthquake.”

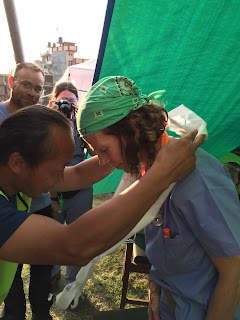

|

| Jane volunteering in Nepal for the devastating earthquake. |

In September 2017, Jane deployed to Jacksonville, Florida

and Charlotte Amalie, St. Thomas, in the U.S. Virgin Islands, to help victims

of Hurricane Irma. It was still raining in St. Thomas and trees and twisted

power lines littered the streets. The island had no power.

In Jacksonville, the storm surge had not receded entirely

days after the storm. The volunteers went to visit an elderly couple who had

shuttered themselves into their home. They both were in declining health, and

the home had been in the family for decades. The couple was determined not to

be uprooted. Mold had begun growing on the walls and the scene was heartbreaking,

Jane says. They respected the couple’s wish to stay. The two had lost so much

and Jane didn’t want them to lose their dignity. The volunteers opened doors

and windows, set up a dehumidifier and some fans to get fresh air moving. They

made sure the couple had plenty of drinking water and knew who to call for

help.

As is too often the case with disasters, there can be so

much sadness that sometimes it is difficult to know what to say. After

Hurricane Irma, a woman came in to get her vital signs checked. It turned out

she and her family had lost their home when Hurricane Harvey struck Texas a

month earlier. Then the temporary housing they had found in Florida was wiped

out by Hurricane Irma. She and her husband and two children had been living in

their car when social services took their children away. In the midst of all of

this, she had a stroke. Jane convinced her to go to the hospital and the

volunteers also guided her to the Federal Emergency Management Agency and local

social services for assistance finding her children.

But there was also joy in the smallest of things. Jane

recalls an elderly woman in a shelter in St. Thomas. The woman was blind,

unable to walk, and terminally ill. She’d been in hospice care before the

hurricane, but shelter workers couldn’t reach the hospice so she was not

receiving any pain medication. But she never complained. One day she told Jane

she’d really like some strawberry-vanilla ice cream. Here they were, in the

middle of an island in blazing heat without power. But it was the one thing

she’d asked for. Jane found a car and driver and they negotiated the debris,

moving at a crawl to the only open grocery store. Most of the shelves were

empty but unbelievably there in the freezer was one quart of strawberry-vanilla

ice cream. They inched slowly back to the shelter through snarled traffic and

brutal heat and somehow the ice cream didn’t melt. Jane joyfully handed it to

the woman.

|

| Jane volunteering in Nepal for the devastating earthquake. |

“Her face opened into the most magnificent smile as she felt

the cold container in her hand and seconds later tasted the ice cream,” Jane

recalls. “It was magic.”

Here at home, Jane deploys most Monday nights as an EMT and

EMS Lieutenant with the Glen Echo Fire Department. A fair number of calls are

for cardiac emergencies. Administering CPR is hard and scary, although training

tempers the fear. As a crew, everyone is working together like mad trying to

revive the patient. It’s exhausting, physically and emotionally. But on those

occasions when you are able to bring someone back after a heart attack? It’s

beyond amazing, she says.

Jane helped develop the Advanced Life Support (ALS) program

at the Glen Echo Fire Department. ALS provides a higher level of pre-hospital

care for the most severe medical emergencies, such as unconscious patients and

cardiac events. It requires a vehicle equipped with more sophisticated and

expensive technology, such as a 12-lead cardiac monitor. Jane and the fire

chief met with Montgomery County officials and proposed a pilot program. Their

station would raise the money to pay for the equipment and train volunteers to

staff the vehicle. After six months, the pilot was declared a success and

became permanent.

At least once a week, Jane volunteers at the JSSA (Jewish

Social Service Agency) hospice. She also visits two people who were diagnosed

with six months or less to live several years ago. They left the hospice

program, but she continues to visit them.

Jane often brings her Yorkie, Callie, with her. Callie went

through the PAL (People Animals Love) certification program and is trained for

hospice care. Patients love Callie: she’s eight pounds of affection. She will

crawl right into bed with someone, lie against them, cuddle and lick them, Jane

says.

|

| Jane volunteering in Nepal for the devastating earthquake. |

Jane also brings along a body tambura, a musical instrument

developed in India to help alleviate the pain of patients in hospices that

can’t afford pain medication. The instrument is placed on the person’s body. A

study at St. Joseph’s Hospice for Dying Destitute/South India found the

patient’s pain was cut in half after a relatively brief exposure and cut in

half again the next day. Jane contacted the study’s author and found she could

get a body tambura in Germany -- and had one made.

Jane’s interest in hospice care was sparked by the extremely

different experiences of her father and mother at the end of life. Her father

died in 2002 after a drawn-out battle with colon cancer. Jane recalls the

hospice caregivers that came to her parents’ home lecturing her father about

dying instead of listening to what he had to say. It broke him and all of the

family, she says.

Ten years later, her mother came to live – and die – in Jane

and her husband’s home. Her mother’s doctor, who was associated with the JSSA,

made house calls and guided them through the hospice process with kindness and

understanding – as well as enormous competence.

“After that experience, which I would characterize as a good

– even healing – death, I became an evangelist for dying well,” Jane says. “The

hospice team can make all the difference.”

Jane’s mother took her final breath within seconds of the

earthquake that struck Maryland in August 2011. Jane’s son had just moved back

from California and had the presence of mind to tell everyone to get to a

doorway. A little while later, Jane and a few close women friends and family

gently washed her mother’s body, all the while singing to her. As Jane sat by

her mother, more friends began showing up with fresh flowers and herbs from

their gardens and they lay them on and around her mother’s body. Some friends

played music. After the sun set, it seemed the right time to bring her mother’s

body out and as they emerged they found people with candles lining the path

from house to street.

“That set the tone for my work in hospice, really,” Jane

says. “The possibility of a beautiful experience

around death.”

Jane is one of 11 master trainers for Maryland Medical

Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment. MOLST is a document that captures

people’s end of life wishes. It goes way beyond its predecessor, the Do Not

Resuscitate Order. It captures a patients’ wishes for a host of treatments,

such as whether they want feeding tubes to be put in or to be transported to a

hospital. Jane and the other master

trainers travel around the state educating health professionals, assisted

living facilities, and the public in how to use the MOLST form.

|

| Jane was named Montgomery County, Maryland’s Volunteer of the Month earlier this Spring. |

Jane, 57, has two masters degrees: one in social work and

the other in government. She is the senior editor and writer at the U.S. Census

Bureau. She lives in Bethesda, MD with her husband, Harry Lewis, and their two

Yorkies, Callie and Cruiser. Her one adult son is engaged and Jane says she’s

looking forward to grandchildren.

The third of four sisters, Jane says her parents chose to

settle in Chevy Chase because they believed the Washington area was ground zero

for civil and human rights volunteer work. Jane’s father, Dr. Earl Callen, a

college physics professor and department chair at American University, started

the American Civil Liberties Union of the National Capital Area. He was also on

the Helsinki Watch Committee, whose mission was to monitor the former Soviet

Union’s compliance with the Helsinki Accords, agreements to accept the

post-World War II status quo in Europe.

|

| Jane Callen |

He regularly traveled back and forth to the Soviet Union to

try to help “Refusniks,” -- scientists being persecuted and prevented from

leaving. Dr. Callen frequently testified before Congress on this and other

issues. He also was an outspoken anti-war activist and was frequently

interviewed because, as a physicist, he could provide unique insight into

nuclear war.

Jane’s mother, Anita Callen, was a stay-at-home mom and her

quiet presence was the yin to her father’s yang, Jane says.

Jane recalls bouncing on her father’s shoulders amidst a sea

of people as they headed toward the Lincoln Memorial, joining Martin Luther

King Jr.’s March on Washington. It was her father’s 39th birthday –

August 28, 1963. She knew they were among a minority of white people and that

it was important to be there, to stand up for civil rights. It was one more lesson

on the importance of taking action, a father-to-daughter message that has

shaped her life.

“That was such an important lesson, taking action not for

self-gain but for a greater good – without regard to personal risk,” Jane says.

“Throughout his life, my father demonstrated the importance of always showing

up.”

No comments:

Post a Comment